A Look at Why English has Weird Spelling

English spelling is funny. Really funny. So, following on from my poem about the strangeness of English spelling, I wanted to focus on one of the largest reasons why it is so weird.

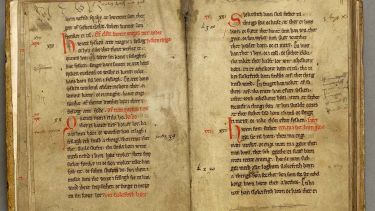

When my Early Englishes module began, we studied Middle English â which is the precursor of Modern Day English and not something from Middle Earth. Something glaringly odd popped out at me. Yup. Itâs spelling, but you knew that.

Letâs use the wonderful word <woman>, which was a very common word back then and remains as such. This word was initially spelt in one or two ways, <womman> and <womane>, and also appeared in the more familiar orthography (spelling system) of <woman>. Okay, it has a couple of spellings, so what? The other two spellings probably merged into the more common contemporary spelling of <woman>, right? Wrong.

Looking at the Middle English compendium, you can see that there are even more variants such as <wommane>, <wommon>, and <wommone>, as well as <womon>, <waman>, and <vimman>. Not to mention <wmonne>, <woiman> and <ummanne>, and thereâs also... I have made my point. Here, there have been twelve common variations upon the spelling, or orthography, of <woman>, but in Middle English there appear to be well over twenty. There also seems to be âantiqueâ words from earlier Englishes that fell out of favour during the Middle English period almost entirely. Some entries are still unknown as to whether they are meant to mean <woman> or something else entirely. Overall, there appears to be around forty different ways to spell the singular version of woman and another thirty entries for its plural counterpart.

Thatâs right. Seventy-plus ways to spell the word woman in those days, but today, we have two â which most of you will be thankful to hear. The singular, <woman>, and plural, <women> which would be written âphoneticallyâ as /wÊmÉn/ and /wÉẂmÉẂn/ respectively. So did they just spell things as they pleased? Did they spell the way that looked and/or sounded right to them? You may all be surprised to hear that this is basically the truth. There was no real sense of correctness or uniformity in spelling, and to make matters more complicated, there is also the concept of âEye Dialectsâ to deal with.

Eye dialects are based on real, regional dialects. It is the same with regional dialects today in that there are phonetic differences in the way certain things may sound, and with Middle English, these dialectal differences would pose different âsetsâ of rules on how individuals of these groups preferred to spell given words. These sets of rules based on regional dialects are what eye dialects are, and to make things just a little more hectic, it is known that a lot of dialects have âlevelled offâ over time, meaning that there were many more regional dialects, and therefore more eye dialects.

If someone came up with a new way to spell and it caught on in a particular area, then we just had yet another spelling for the same word. This do-what-you-want approach to spelling has made it extremely difficult sometimes for historians and linguists to decipher what old texts may mean, as one or more spelling for one word could well have coincided with one or more spellings with another. However, it did mean texts could have their scribes more easily identified as from a particular place as a result of the plethora of dialects.

A spelling reform of English in America caused some variation across spelling such as the popularised American usage of <z> (I should have written popularized instead) and the deletion of <u> in <colour> amongst many more differences. English in Britain has been more resistant to such reforms and did not undergo a major upheaval where others languages have â Dutch for example. Due to the vast pool of English spellings available, when standardisation was proposed to make things more uniform, a diverse breadth of spellings were chosen, resulting in weird spellings that rhyme by voice but not by eye. To paraphrase a tad inexactly, you used to be able to spell how you like, so if youâd like to return to this hellishly confusing period of English, just tell your tutor that you are practising your Middle English spelling â though you might get marked down kwaite a bitt.

If youâre wondering why I have used the brackets â<â and â>â, this will be fully explained in the next blog where I can show you how to play around with silly English spelling.

Written by DP, Digital Student Ambassador.